How Can Design Thinking Influence Collaboration in Practice

“Design is all about learning from doing, that’s how we evolve to the best solution.”

Design thinking is described by Tim Brown as “a human-centred approach” to the creative process. It is a holistic interaction between ‘designer’ and client — which moves away from short-sighted needs and defined roles. But what happens when the lines between designer and client begin to blur in practice? Does the process fall down? Or can the encounter based on commission evolve into one of collaboration?

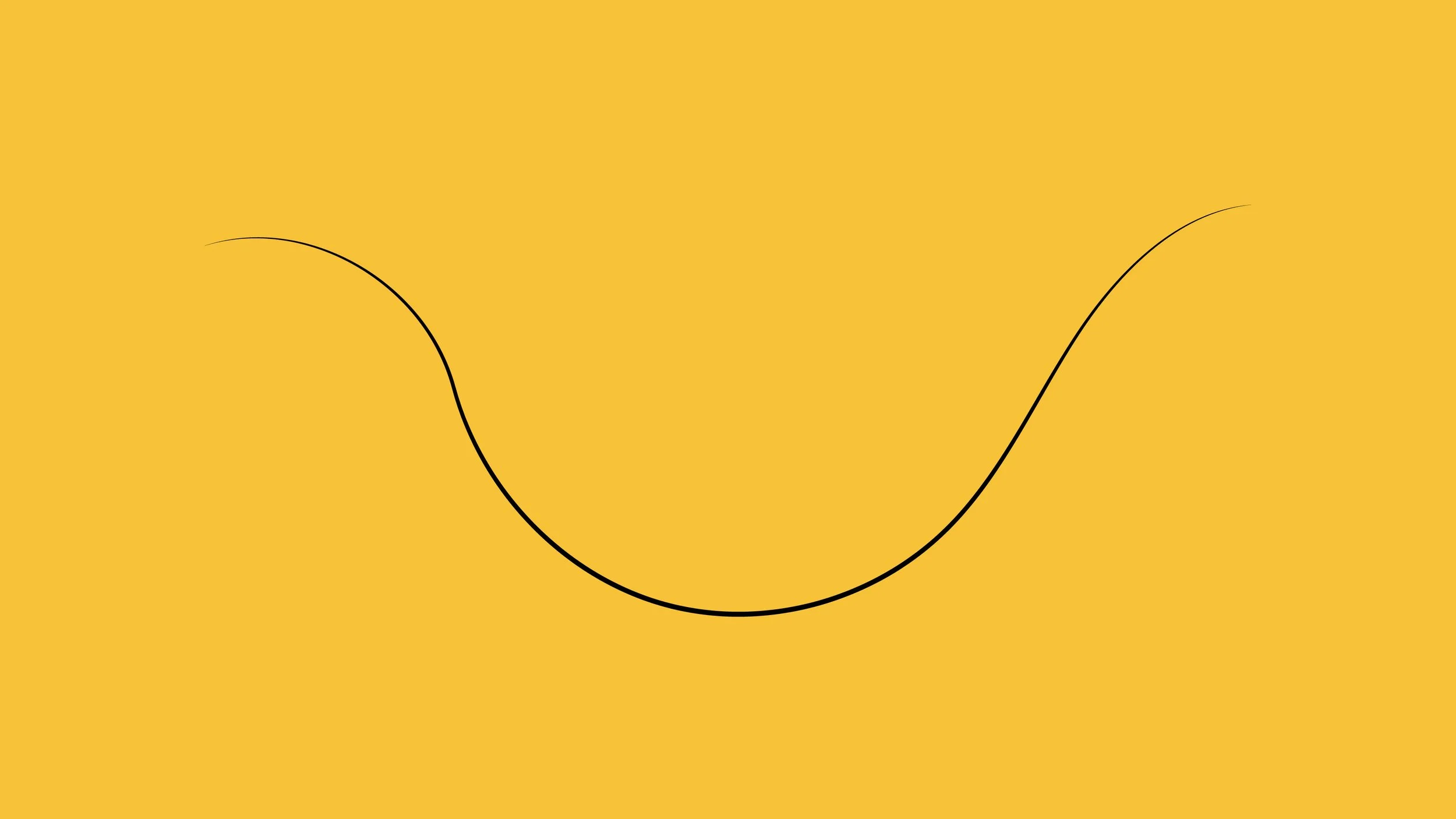

Earlier this year Indigenous was approached to develop a visual identity for an independent film company. Some time passed between an initial deep dive with the client and the development of a working brief. The purpose of a deep dive in design thinking is to primarily ask questions, not question the client. What do you like? What derives meaning? What are your points of reference? Why do you want this? Do you need it? By asking questions the goal is to better understand the clients needs and wishes — before formulating a concept and proceeding to a conclusive design. This is perhaps best illustrated in Damien Newman’s The Design Squiggle (see fig. 1.). In the case of a visual identity it can initiate a process of elimination for colours, fonts, styles — providing a personalised framework to develop prototypes. If a client feels as though they have been listened to, they will see their input in the conceptual stage, and have an idea of how the solution may look. Newman’s sketch visualises the weight of a research-led approach to the design process. In short: the better the in-depth research and initiation, the more straightforward the route to a desired solution (see fig. 2.).

In the initial meeting between creative and client, the boundaries of engagement are established in order for creative games to be played. As Tim Brown points out in his talk Tales of Creativity and Play, we need rules to play without games descending into anarchy (Brown, 2008). But like many forms of play, there is a yearning for inclusion. It is not uncommon for a client to want to go away and explore the results of this analysis before proceeding further. This can be concerning for the creative professional. The client may feel emboldened by the clarity drawn from the dialogue and think they can develop ‘solutions’ themselves. But is this a negative outcome, or just a part of the contemporary creative dialogue?

When receiving the brief from Lieder Film, the reflective questions were answered. The goal was to have a visual identity that had references to cinema, placing the brand within the movie channel sphere, but distinguishing it from popular outlets. There were points of reference, and levels of meaning attached to them. But then the brief went further; identifying the exact colour code of red, font choice and even offered a prototype that had ‘meaning’. The clients new-found creativity posed some interesting points. Equipped with a version of the desired solution, is this a threat to the designers role? Or is this again just an evolution in a collaborative design thinking process?

In Relational Aesthetics (2002), Nicholas Bourriaud says that: “Artistic activity is a game, whose forms, patterns and functions develop and evolve according to periods and social contexts: it is not an immutable essence.” (Bourriaud, 2002, p.11). The same could be said in professional contexts. Roles can be intermittently fluid. They are not exclusive states. Creativity is not a job, it is how half of the brain functions. Creative tools are more accessible than ever for non-professionals to express their ideas. While this can be viewed as a threat in the creative industry — the reality is that expectations are evolving. Miwon Kwon identifies this in the arts sector, stating: “What they (artists) provide now, rather than produce, are aesthetic, often ‘critical-artistic,’ services.” (Kwon, 1997, p.103). In design terms, this notes a key progression from designing things to consulting through design thinking. The end goal may be for a similar purpose, but the process leads.

While some of the ‘big’ decisions were offered by the client in this project, in reality a lot of work remained to fine-tune and finesse the prototype into a professional visual identity. The word ‘Lieder’ is written in Courier; a standard typeface for scriptwriting (an element of meaning). To compliment that we decided to change the font on ‘FILM’ to Montserrat, a sans-serif typeface which could also be used whenever Courier was too overbearing in further uses of text. The framing, alignment, line weight and character spacing all encompass mathematical values from the Fibonacci sequence and frame ratios to create a spatial harmony. It differentiates the level of detail a professional can go into beyond basic aesthetics — while acknowledging that the design is the result of collaboration in its conception.

The real pleasure came in explaining these invisible details, which increased the clients own attachment to the end result. Once complete, there is also the transfer of ownership and responsibility. The longevity of the visual identity is determined in the brands success, but also in its personalised value. If a client considers the work to be by someone else, then the commitment to continuity will not be sustainable.

Creative professionals are increasingly needed to be multidisciplinary: to be a researcher, commissioner, keeper, interpreter, producer, collaborator (Hoare, 2016). The designers key asset today is the ability to facilitate creative thinking with others, more than the development of a specialised portfolio. Miwon Kwon’s description of the contemporary artist is similar, saying it is not about being “…a maker of aesthetic objects…” but “…a facilitator, educator, coordinator, and bureaucrat.” (Kwon, 1997, p.103).

Richard Serra once said: “ Art is not democratic. It is not for the people.” Design thinking is democratic, and therefore not in service to create art. It is not the singular vision of the dictatorial client or protective designer, but an algorithm of decisions taken through human interaction. Through design thinking the client can also be a collaborator, commissioner and creator in the design process.

References

Bourriaud, N (2002) Relational Aesthetics. Paris: Presses du Réel.

Brown, T (2008) Tales of Creativity and Play. [Pasadena: Art Center College of Design 07/05/2008]. At: https://www.ted.com/talks/tim_brown_tales_of_creativity_and_play?language=en (Accessed on 09.12.20)

Hoare, N (2016) The New Curator. London: Laurence King Publishing.

IDEO Design Thinking (no date) Available at: https://designthinking.ideo.com (Accessed on 08.12.20)

Kwon, M (1997) ‘One Place after Another: Notes on Site Specificity’. In: October, Vol.80(1), pp 85-110

Newman, D (no date) The Design Squiggle. Available at: https://thedesignsquiggle.com (Accessed on 08.12.20)