Quantifying Design Thinking through Impact Measurement

“We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.”

Design thinking has matured into a qualitative process to tackle what Buchanan (1992) calls: “wicked problems”. Extending beyond the creative sphere, design thinking is now a valid method for government strategy, educational reform and corporate structure (Fyffe & Lee, 2016). Using a human-centred approach (Brown, 2009), design thinking democratises creativity beyond professional practices, allowing anyone to fulfil their potential (Kelley and Kelley, 2013). But can a mindset, or creative process be quantified? And how can it lend weight to existing methods?

What Buchanan (1992) refers to as ‘wicked’, is the complexity behind human-centric challenges that arise within a diversity of interlinked spheres, levels and stages of being, becoming, doing and happening. Meaning, they are complex and ‘wicked’ precisely because they multi-dimensional. Within a society that has espoused a linear paradigm of separation, dualism and division, evolving into an era where it is fully recognised in all policy fields that everything is interconnected, systems or systemic thinking has become an essential quality for evaluating, understanding and reconciling the known and the unknown. In that sense, design thinking is bound to systems and complexity theory, and enables us to recognise existing and emergent patterns that we would otherwise not notice under a linear, one-track minded or conventional thinking cap — and give them a different, more nuanced meaning.

There are few greater human-centred, or ‘wicked’ problems than the challenges collaborator and regular client RiseUp face — working in UK prisons to provide convicted criminals with the tools to accept their mistakes, identify problems and be better equipped to improve their decisions going forward. The RiseUp programme deals directly with complexity — emotional, intellectual, psychological, cognitive, environmental, institutional, societal, etc. — negotiating the journey between the known and the unknown.

Like design thinking, their 12-part course is itself a creative process; using artistic expression to facilitate positive change in the participants. Its aim is primarily to empower them to deconstruct their learned behaviour before they can even envisage their agency and transform themselves into their chosen individual potential.

While compiling a report for one of their recent programmes, RiseUp Business Director Stuart Coady reviewed the first results of a new Impact Measurement Survey they designed in partnership with The Youth Endowment Fund and impact specialists, RealWorth. He said: “At first we didn’t know how to interpret the data. We knew from oral and written feedback that we had made a positive impact, but we weren’t sure how this would show-up visually in the report.”

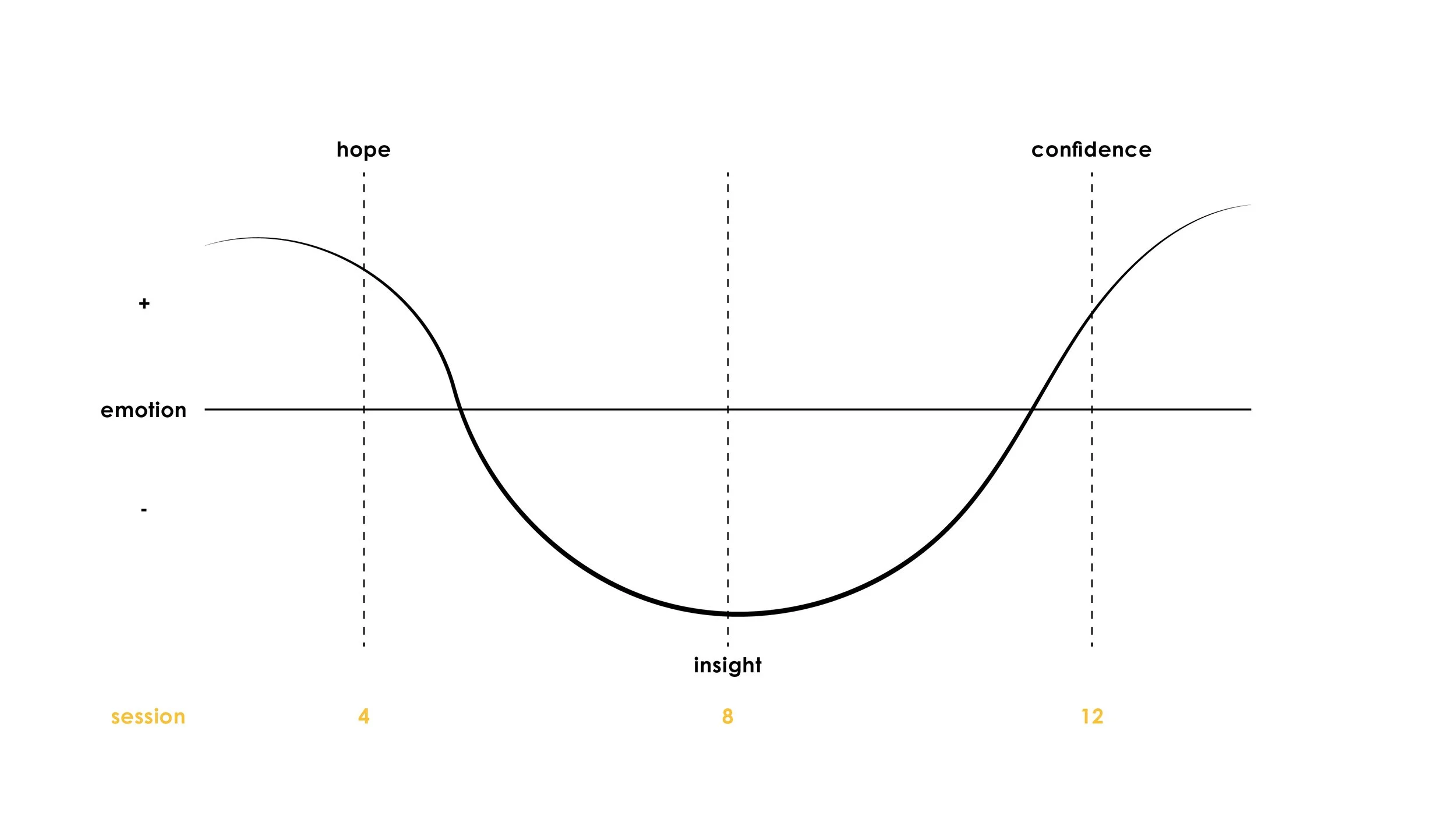

During the handover of information for Indigenous to edit and format, we got into a discussion about illustrating data from the Impact Measurement Survey. For privacy reasons the results of which cannot be disclosed, but the insight of the undertaking can be elaborated on in further detail. While preparing a quick mock-up graph, a pattern started to emerge; with a dip in positive scores at the middle part — contrasting between higher initial and summative scores.

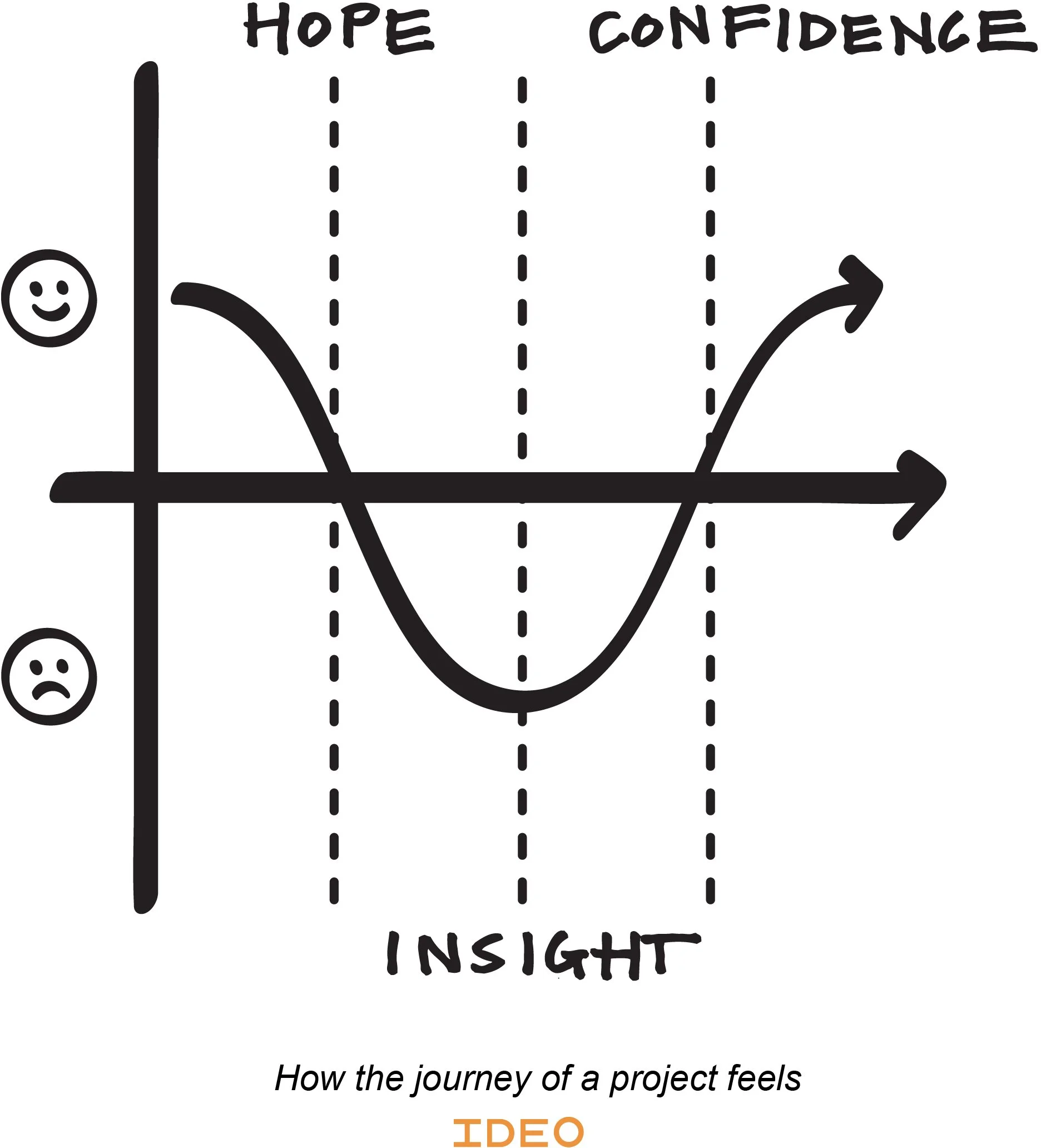

With knowledge of design theory, the trough brought immediate comparison with IDEO’s illustration How it Feels (see fig. 1.). Stuart continues: “It was when Bryn at Indigenous compared the data with the emotional journey of a design thinking approach that things started to make sense.” The journey from Hope to Confidence in creative processes often encounter a bottoming-out — where failure and self-awareness provides Insight, and a realisation that new ways of thinking and doing are needed to progress (IDEO Design Thinking, n.d.).

This emotional context correlates with RiseUp’s own model, which is based on Joseph Campbell’s The Hero’s Journey and the Theory of Change, devised by Professor Erik Bichard. Creative Director Ashleigh Nugent explains: “Session 8 is titled Death + Rebirth. It is where the participants let go of their past identities, stories and setbacks. While inputting data from our Impact Measurement Survey, we were amazed, and delighted, to see how perfectly the results align with the design thinking model. We saw individual scores for self-awareness and emotional control drop during the Insight moment of session 8, only to rise exponentially by the end of the course.”

At this stage of the RiseUp programme, participants have been given the tools to re-design themselves emotionally, but lack the real-world experience to use them. Moreover, session 8 is the stage in which their starting point, what they thought was their identity has been challenged to its core. This democratisation of creative confidence (Kelley and Kelley, 2013) increases the potential risk in change, and an initial loss of Hope. It draws comparison with design critic Don Norman (2010), whose biggest reproach of professional designers tackling the big issues is people ”thinking they know things they don’t." (ibid). While they may be equipped with agile methods and practices, they can lack the knowledge and experience of the context in which they apply them.

A potential weakness in creative confidence, can conversely be considered a strength. Design thinking uses iteration to gain Insight when faced with human-centric, ill-defined problems which cannot be solved first time. Likewise, the RiseUp programme is not a linear journey but a circular one — and the Hero's Journey is itself a wheel of transformation — it operates through spirals of revelations, discoveries and epiphanies, within a framework that fosters focus on personal realisation. This is one of RiseUp’s distinctive features — empowering individuals with the Confidence to change themselves, as opposed to prescribing a standard direction for all.

This — the cyclical journey of discovery through the known and the unknown — is what the design thinking illustration is capable of capturing, especially at the point of session 8 in the RiseUp programme — the pupation stage of transformation, when one realises that everything we once thought we knew about ourselves does not determine who we will/want to be or can become. It provides us with a snapshot of the moment participants understand that whilst they knew who they were, they have yet to know who they want to be and become. As discussed earlier, session 8 is indeed the void — death and rebirth — when the field of possibilities opens up to consciousness, and decisions are being made as to which direction or form our awareness is going to take.

In the humanities and social fields, it has not been possible to properly quantify human experience. Yet through Impact Measurement Surveys, we can identify a timeline of transformation. Design thinking, based on a theory of iteration and development, supports the theory of change behind the RiseUp programme that is a map for personal transformation through self-awareness — and for the observer, we have been able to 'see' where/when the moment of truth may be happening. It could have been interpreted as a negative outcome under a linear theory of change, but not under a design thinking theory of change.

The RiseUp course is in effect ‘designed’ to change mindsets and behaviours. The parallels with design thinking highlight that Insight cannot be expected in behavioural change without a deviation from the status quo. Consequently real growth cannot be measured through a linear increase of scores. This backs-up the qualitative value behind design thinking methods, with quantitative data from a real-world exercise whose objective is to improve conscious behaviour in people on the margins of society.

For design thinking, it is potentially another string to its bow, and demonstrates once again that creativity can be a tool for anyone to flourish.

This article is co-authored with Alexandra Pimor, Founder of SoaNoia and RiseUp Director. With contributions from RiseUp Creative Director, Ashleigh Nugent; and Business Director, Stuart Coady.

Indigenous wishes to thank all at RiseUp for their time and assistance in writing this article.

References

Brown, T. (2009). Change by Design. New York: HarperCollins.

Buchanan, R. (1992). Wicked Problems in Design Thinking. Design Issues, 8(2). 5-21.

Fyffe, S. & Lee, K. (2016). How Design Thinking Improves the Creative Process. Retrieved from https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/how-design-thinking- improves-creative-process

IDEO Design Thinking. (n.d.). Design Thinking Defined. Retrieved from https:// designthinking.ideo.com

Kelley, D. & Kelley, T. (2013). Creative Confidence: Unleashing the Creative Potential Within us All. New York: Crown Business.

Norman, D. (2010). Why Design Education Must Change. Retrieved from https://www.core77.com/posts/17993/why-design-education-must-change-17993

RiseUp CIC. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.riseupcic.co.uk